How Arduino builds a sketch?

Arduino is one of the most popular ways to start learning embedded systems. At the same time, you can find plenty of debates online about whether Arduino is a good choice for that (like “Is there anything wrong with Arduino?”, “Why engineers hate Arduino?” [1], [2] ).

While the list of arguments from Arduino “opponents” is quite long — and some of their points are completely reasonable — I want to prove that you can learn just as much with Arduino as with any other embedded platform, as long as you avoid blindly relying on the Arduino API and stay curious to explore what’s happening under the hood. That’s why I am creating the Arduino Internals series.

As a starting point, let’s take a closer look at what happens when you build a sketch in the Arduino IDE.

Assumed knowledge

I assume you already know how to compile and flash an Arduino board with the Arduino IDE, but haven’t yet dived into the internals of the compilation and flashing process.

My setup

- Arduino UNO R4 WiFi board

- Arduino IDE 2.3.6

- Ubuntu 24.04

If you’re using a different board, IDE version, or operating system — don’t worry! You can still follow along. Some details may just look a little different on your setup.

Understanding Arduino build process

Building an Arduino sketch in the IDE seems as simple as clicking one button, but under the hood it performs several important steps — some common to nearly every embedded development environment, and others unique to Arduino.

This simplicity is great for beginners, but if you want to take embedded systems seriously, it’s worth understanding what really happens behind the scenes. Once you move beyond Arduino’s friendly abstraction layer, you’ll need to know how the build process works — because without it, things may not behave as you expect.

What you will learn?

After reading this article, you will:

- understand the standard build flow in embedded software development,

- learn about the additional steps performed during the Arduino build process,

- know where to find the build files, caches, and linked libraries,

- discover what language Arduino sketches are actually written in.

Let’s get started!

Let’s build a sketch together and go step through the build process. We’ll pretend we know nothing and analyze the build output to see what the Arduino IDE actually did.

Opening an example sketch

Open the Arduino IDE and select the correct board from Select Board menu. In my case it’s Arduino UNO R4 WiFi. Load the Blink example and save the sketch in your sketchbook.

This example consists of a single file: Blink.ino.

Files with the .ino extension contain code written in the Arduino language [1].

You may notice there is no main function in this code, yet it still compiles.

What exactly is Arduino language?

According to the official documentation the Arduino language consists of:

- set of functions like

digitalRead,digitalWriteetc, - predefined constants such as

HIGHandLOW, - basic data types like

array,bool,int, - special sketch functions such as

loop,setup…

And so on. You can just read the full list on the official page. There’s also a brief note mentioning that Arduino is based on C++. Well — we’ll see at the end of our investigation, if Arduino language is actually a language… or just a C++ in a disguise.

Triggering the build

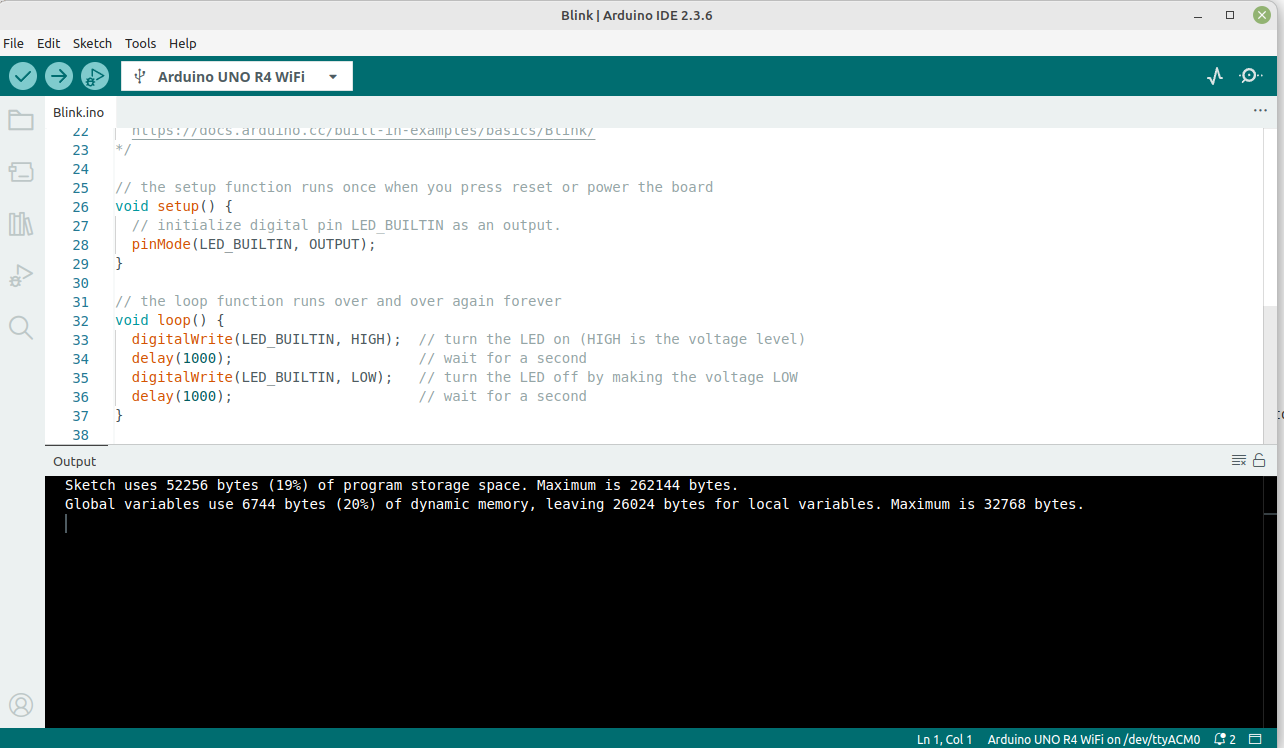

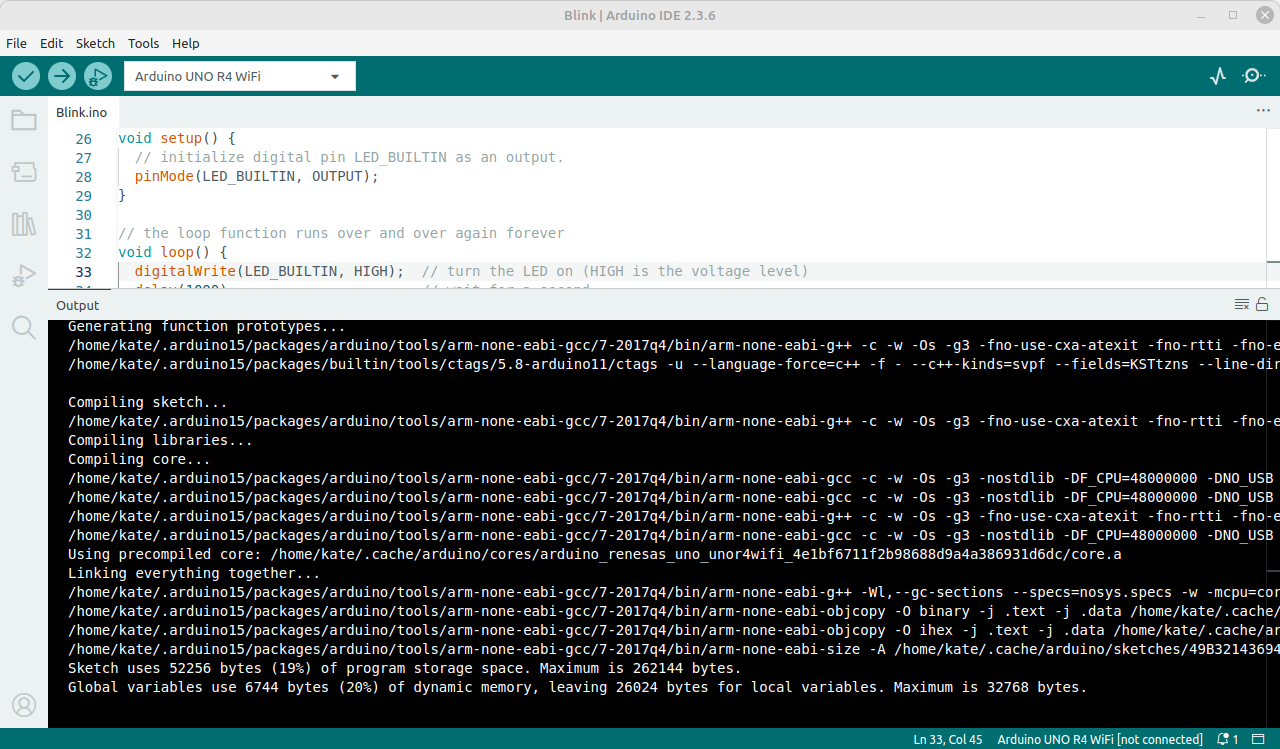

We are ready to build this sketch. Click Verify/Compile and observe the Output window.

It looks like the sketch has been built successfully and is ready to upload to the board. You only see two lines of output because the Arduino IDE hides most of the build details by default.

Enabling verbose output

To understand the build process better we need to enable the verbose output in IDE.

To do so, go to File → Preferences and check Show verbose output setting for both compiling and upload. When you compile again,

the output will be complete.

Let’s read it line by line.

Board and package identification

In embedded software development, the compilation process is always target-dependent. Each hardware architecture — such as ARM or AVR — requires its own dedicated cross-compilation toolchain. In addition, the appropriate version of the hardware libraries must be selected and linked. Therefore, the target board must be identified before the build begins.

Arduino handles this step automatically. It looks at the board you’ve chosen in the Select Board menu and configures the build accordingly. This ensures that the compiled code will match the board’s architecture, hardware, pin mapping etc.

This board identity is called FQBN (Fully Qualified Board Name) and looks as follows:

FQBN: arduino:renesas_uno:unor4wifiFQBN is unique for each board. It consists of three segments:

- Vendor:

arduino(it’s official Arduino package) - Architecture:

renesas_uno(Renesas-based boards family) - Board:

unor4wifi(exact model: Arduino Uno R4 WiFi).

If you choose wrong board, the code may compile but fail at runtime, or compilation may fail.

Error Compilation error: Missing FQBN (Fully Qualified Board Name) means you have not selected any board from menu.

Arduino specific directories

In a typical embedded development environment, the build process produces various artifacts (object files, binaries, maps, etc.), which are stored in a user-defined or default build directory. Knowing where these artifacts are located allows developers to:

- see which source files are compiled,

- inspect intermediate and output files (e.g.,

.oor.elf) to diagnose build or linking issues, - analyze additional information from

.mapfile.

In most embedded IDEs, the user also knows and can control where all linked libraries come from.

In Arduino, location of build artifacts and used libraries is not immediately obvious, since these files are placed in several hidden directories. However, their locations can be found in the build log. Let’s take a quick look at these directories.

Arduino15 directory

Arduino15 contains, among others:

- installed board packages (cores, board definitions, hardware specific libraries),

- global libraries that Arduino automatically installs,

- tools needed for development with Arduino (like toolchains and flashing tools),

- user preferences, customized settings, etc.

The exact location depends on your operating system [1].

Board packages

The build log shows the directory where the target board’s related files are located, for example:

Using board 'unor4wifi' from platform in folder: /home/kate/.arduino15/packages/arduino/hardware/renesas_uno/1.4.1

Using core 'arduino' from platform in folder: /home/kate/.arduino15/packages/arduino/hardware/renesas_uno/1.4.1Inside this directory, two files deserve special attention: boards.txt and platform.txt.

boards.txt

The boards.txt file lists all boards supported by this platform. Each board has its own section with key-value pairs that define how to compile, upload, and debug for that target.

Here’s the entry for the Arduino UNO R4 WiFi:

##############################################################

unor4wifi.name=Arduino UNO R4 WiFi

unor4wifi.build.core=arduino

unor4wifi.build.crossprefix=arm-none-eabi-

unor4wifi.build.compiler_path={runtime.tools.arm-none-eabi-gcc-7-2017q4.path}/bin/

unor4wifi.build.variant=UNOWIFIR4

unor4wifi.build.mcu=cortex-m4

unor4wifi.build.architecture=cortex-m4

unor4wifi.build.fpu=-mfpu=fpv4-sp-d16

unor4wifi.build.float-abi=-mfloat-abi=hard

unor4wifi.upload.tool=bossac

...These settings ensure that once you select your board from the Select Board menu, the correct toolchain, compiler flags (such as MCU type and clock speed) and upload tool are selected automatically.

Advanced users may feel need to modify the boards.txt contents, to i.e. add new board or customize some build options. Just remember that such changes will be lost after Arduino IDE update!

platform.txt

Another important file is platform.txt. This file defines the command patterns (recipes) that tell Arduino exactly how to compile, link, and package a sketch for a specific platform.

It defines:

- the commands used for compiling and linking,

- how archives and output files are created,

- the flags and options passed to the compiler,

- and the commands used to calculate the size of the final program.

Basically, this is the most important file telling us how Arduino builds a program. Unlike traditional C/C++ projects, there is no Makefile in the Arduino build system — instead, platform.txt provides all the recipes that define each step of the build process.

Behind the scenes, the Arduino IDE uses arduino-cli to build sketches according to these recipes. The arduino-cli tool expands and executes the command patterns defined in platform.txt. For example, the recipe for compiling a C source file is as follows:

## Compile c files

recipe.c.o.pattern="{compiler.path}{compiler.c.cmd}" {compiler.c.flags} -DARDUINO={runtime.ide.version} -DARDUINO_{build.board} -DARDUINO_ARCH_{build.arch} -DARDUINO_ARCH_RENESAS -DARDUINO_FSP -D_XOPEN_SOURCE=700 {compiler.fsp.cflags} {compiler.tinyusb.cflags} {compiler.c.extra_flags} {build.extra_flags} {tinyusb.includes} "-I{build.core.path}/api/deprecated" "-I{build.core.path}/api/deprecated-avr-comp" {includes} "-iprefix{runtime.platform.path}" "@{compiler.fsp.includes}" -o "{object_file}" "{source_file}"Toolchains

Inside the Arduino15’s tools directory, you will also find the cross-compilation toolchains used to build sketches for different microcontroller architectures.

In my setup, two toolchains are installed:

.arduino15/packages/arduino/tools/arm-none-eabi-gcc, for ARM based boards, like Arduino UNO R4 WiFi,.arduino15/packages/arduino/tools/avr-gcc, for AVR/Atmega based boards.

The main components of toolchain are compiler, asembler and linker. Everything that is required to build for a specific architecture.

Why we need cross compilation toolchains? When building application for embedded devices, the compilation happens on the host — your development computer running the Arduino IDE — not on the target device itself.

The host (PC) typically uses an x86_64 processor with its own instruction set and operating system. The target device (like an Arduino board) uses a completely different architecture — for example ARM or AVR.

To generate code that runs correctly on the target, we need a cross-compilation toolchain: compiler tools that are able to produce binaries for a different architecture than the one running the compiler.

Most Arduino boards use either ARM or AVR architectures, which is why you’ll find these two toolchains installed in the Arduino15 directory.

Arduino core

The Arduino core directory provides the hardware-specific implementation of core Arduino functions.

It is located in the cores subdirectory of your board package, for example:

.arduino15/packages/arduino/hardware/renesas_uno/1.4.1/cores/Each board family, or platform, has its own core, tailored to the hardware and peripherals.

The Arduino core contains, among other files:

main.cpp— defines the startup code that runs before yoursetup()function and repeatedly calls yourloop()function,Arduino.hheader — the main header file included by all sketches,- implementation of interrupts, UART communication, timing functions like

delayand other low-level routines.

Open the main.cpp and browse the logic that Arduino is adding around the code you implemented in the sketch.

Build directory

When you compile a sketch, the build artifacts (i.e. intermediate object files) are not stored in the same directory as your source code. It would make a mess inside your sketch folder, or even made conflicts when building the same sketch for different boards.

That’s why build files are always stored in separate build directory.

In case of Arduino IDE, the build directory is a per-sketch cache, created in a hidden folder.

You can find the path to this build directory in the build log. My sketch was built here:

/home/kate/.cache/arduino/sketches/D7CC1D7CA645BCFE67207C07A05B3A2A/sketch/`.If you open this folder, you’ll see the build artifacts, including:

- object files (

.o), - preprocessed sources (

.cpp), - final binaries (

.bin,.hex,.elf).

Exporting Compiled Binary

If you want to have the compiled binaries in your sketch folder, click Sketch → Export Compiled Binary option from Arduino IDE menu.

This will build your sketch and place a copy of the .hex, .bin, .elf and .map inside the sketch sources

folder so it’s easy to find later.

Do you want to move Arduino15 folder? In some cases, you may want to move the Arduino15 folder — for example, to free up space on your primary drive.

To do this:

-

Copy the Arduino15 directory to your desired location.

-

Open the file

~/.arduinoIDE/arduino-cli.yamland update thedirectories:datapath, for example:

board_manager:

additional_urls: []

directories:

data: /home/kate/new-location-arduino15-

Restart the Arduino IDE. It will now use the new Arduino15 location. Verify the build output to ensure everything is working correctly.

-

Once you’ve confirmed everything works correctly, you can safely delete the old folder.

We already discussed board identification and the Arduino specific directories. Let’s move to actual build process.

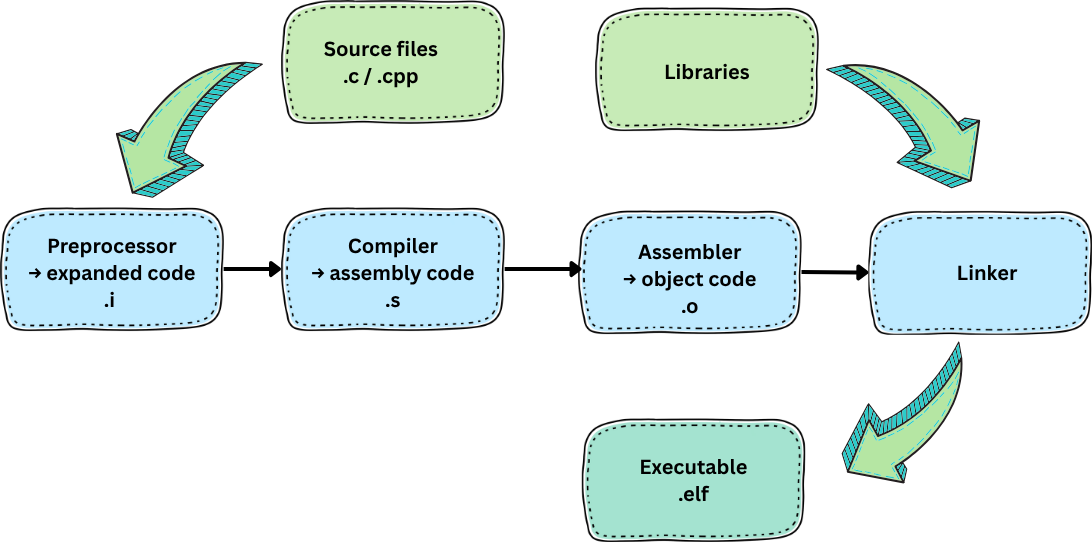

General embedded software build process

At a high level, the Arduino build process is essentially a C++ build process adapted

for embedded targets, and with some Arduino specific features. The general C/C++ build pipeline is presented below:

Now, let’s go through each stage and see how Arduino adapts the standard C/C++ build process for embedded targets.

Preprocessing

The first phase of every C/C++ program build is preprocessing.

In general, preprocessor expands macros like #include, #define, and conditional compilation (#if, #ifdef, etc.).

The output is an expanded source file.

In Arduino, some additional steps are added around preprocessing stage.

Concatenating .ino files

If the sketch contains of multiple .ino files, they are first concatenated into a single .cpp file.

Detecting libraries used

Arduino uses a special build recipe (recipe.preproc.macros [1])

to detect which libraries are required by your sketch.

During this step, the preprocessor scans the sketch for #include directives that reference library header files.

If a matching header is found, the corresponding library is automatically marked as required and included in the build process

— in other words, that library will be compiled and then linked in next stages of build process.

Detecting libraries used...

/home/kate/.arduino15/packages/arduino/tools/arm-none-eabi-gcc/7-2017q4/bin/arm-none-eabi-g++ (...) -E \

/home/kate/.cache/arduino/sketches/D7CC1D7CA645BCFE67207C07A05B3A2A/sketch/MyBlink.ino.cpp -o /dev/nullThe -E flag tells GCC to perform only the preprocessing step —

it expands all macros and headers, then stops before compiling or assembling anything.

For a simple sketch like Blink, this stage isn’t very exciting — it doesn’t detect in any additional libraries. That’s why the build output doesn’t show anything under Detecting libraries used…. But if you open other example sketches, such as those from WiFiS3 or EEPROM, you’ll see how more complex projects trigger detection of multiple libraries.

Generating function prototypes

The next stage in the build process is automatic function prototype generation. In C or C++, each function must be either defined or declared before it’s called. In Arduino, you don’t need to worry about that — you can write functions in any order, without adding their prototypes. How does it work? Arduino generates these prototypes for you!

Here’s what the build log shows:

Generating function prototypes...

arm-none-eabi-g++ (...) -E /home/kate/.cache/arduino/sketches/D7CC1D7CA645BCFE67207C07A05B3A2A/sketch/MyBlink.ino.cpp -o /tmp/1121713208/sketch_merged.cpp

ctags (...) /tmp/1121713208/sketch_merged.cppAgain, the compiler is invoked with the -E flag, meaning only the preprocessor runs.

This is what happens now:

-

Preprocessing

The

MyBlink.ino.cpp(file concatenated of all.inofiles) is input for the preprocessor:#includes are expanded and macros replaces. The expanded file is stored as/tmp/1121713208/sketch_merged.cpp. -

Scanning functions

Tool

ctagsis running over expandedsketch_merged.cpp, to extract function symbols. -

Generating prototypes

Based on the

ctagsresult, Arduino environment inserts forward declarations for you. This way, you don’t need to worry about undeclared functions, functions order, etc. -

Store prototypes into .ino.cpp

The resulting version is stored into

MyBlink.ino.cpp. This is what the compiler will actually use later on.

Your simple sketch (MyBlink.ino):

void setup() {

pinMode(LED_BUILTIN, OUTPUT);

}

void loop() {

digitalWrite(LED_BUILTIN, HIGH);

delay(6000);

digitalWrite(LED_BUILTIN, LOW);

delay(1000);

}gets transformed into (MyBlink.ino.cpp):

#include <Arduino.h>

#line 1 "/home/kate/Arduino/MyBlink/MyBlink.ino"

#line 26 "/home/kate/Arduino/MyBlink/MyBlink.ino"

void setup();

#line 32 "/home/kate/Arduino/MyBlink/MyBlink.ino"

void loop();

#line 26 "/home/kate/Arduino/MyBlink/MyBlink.ino"

void setup() {

pinMode(LED_BUILTIN, OUTPUT);

}

void loop() {

digitalWrite(LED_BUILTIN, HIGH);

delay(6000);

digitalWrite(LED_BUILTIN, LOW);

delay(1000);

}The key differences can be summarized as follows:

#include <Arduino.h>is added,- function prototypes are added,

#linemacros are added — they keep compiler error messages pointing to the right lines in your.inofile. Without them, errors would show up with the line numbers of the generated.cpp, which would be super confusing.

This is the first preprocessing step, unique to Arduino.

Now, sketch/MyBlink.ino.cpp is not yet fully expanded —

you can see this file inside your sketch’s hidden cache.

After that, the standard C/C++ preprocessing takes place when compiler is invoked again in next step —

all #include directives are replaced with the contents of the included files,

all #defines macros are expanded, and the result

is one fully expanded source file ready for compilation.

Compilation

Compilation is where your code is translated into the low-level machine instructions that the microcontroller can actually execute. In other words, your human-readable program becomes something the hardware understands.

Sketch compilation

During this step, the compiler finalizes preprocessing (the standard C/C++ preprocessing that was not yet performed), checks your code for syntax errors and converts it into the object code that can be linked with libraries later.

Compiling sketch...

arm-none-eabi-g++ (...) -c sketch/MyBlink.ino.cpp -o sketch/MyBlink.ino.cpp.oCompiler is invoked with -c flag, which means compile and assemble (don’t link yet).

It also performs the standard preprocessing phase as part of this step.

Input: MyBlink.ino.cpp — the auto-generated sketch with prototypes, includes, and line directives.

Output: MyBlink.ino.cpp.o — machine-code object file, ready to be linked later.

I shortened the compilation command, so it’s not in the snippet above, but in IDE we can observe a lots of compilation flags that were used. Some highlights:

-Os→ optimize for size [1].-g3→ include debug info at max level [1].-fno-rtti,-fno-exceptions→ strip C++ runtime features to save space [1], .-nostdlib→ don’t link against standard system libraries [1].-mcpu=cortex-m4 -mthumb -mfloat-abi=hard -mfpu=fpv4-sp-d16→ target an ARM Cortex-M4 with hardware floating point.-Iand@.../includes.txt→ add search paths for Arduino core and variant headers.- Many

-D...→ defines for board, CPU frequency, Arduino version, etc.

Most advanced IDEs let you change compiler settings like optimization level, debug info, or extra flags right from a project menu.

Arduino IDE is so simple that it doesn’t offer this option: you don’t get a button or menu for that.

If you want to change some settings, you’ve got several ways:

- Edit build recipes: you can change files like

platform.txtorboards.local.txtto change or add your own compilation flags, - modify

arduino-cli.yamlfrom ArduinoIDE folder, - use Arduino CLI directly: the command-line tool gives you more flexibility and can build your sketch with whatever options you like.

At this point, your sketch has been turned into machine code, stored in MyBlink.ino.cpp.o.

This file contains your setup() and loop() code, ready to be linked with the Arduino core and libraries in the next step.

Compiling libraries

All libraries, that were marked as required, are compiled now.

Compiling libraries...For the Blink sketch this step is empty. In the previous phase (Detecting libraries used) no additional libraries were found.

Blink only relies on core Arduino functions such as pinMode, digitalWrite, and delay, which are part of the board core, not separate libraries.

In more advanced sketches the output looks different. For example, in WiFiS3/ConnectWithWPA the WiFiS3 library is detected and its source files are compiled here.

Compiling core

All needed core objects are compiled.

Compiling core...

Using previously compiled file: /home/kate/.cache/arduino/sketches/D7CC1D7CA645BCFE67207C07A05B3A2A/core/tmp_gen_c_files/pin_data.c.o

Using previously compiled file: /home/kate/.cache/arduino/sketches/D7CC1D7CA645BCFE67207C07A05B3A2A/core/tmp_gen_c_files/main.c.o

Using previously compiled file: /home/kate/.cache/arduino/sketches/D7CC1D7CA645BCFE67207C07A05B3A2A/core/tmp_gen_c_files/common_data.c.o

Using previously compiled file: /home/kate/.cache/arduino/sketches/D7CC1D7CA645BCFE67207C07A05B3A2A/core/variant.cpp.o

Using precompiled core: /home/kate/.cache/arduino/cores/arduino_renesas_uno_unor4wifi_4e1bf6711f2b98688d9a4a386931d6dc/core.aThe core is the foundation of every Arduino program (we discussed it in Arduino core chapter). Instead of recompiling the same core files every time you build, the Arduino IDE uses precompiled objects from a cache to speed up the compilation.

Linking

Once all the individual files are compiled, the Arduino build system needs to link them into a single program. I shortened the link command to present only the most important stuff:

arm-none-eabi-g++ \

-mcpu=cortex-m4 -mfloat-abi=hard -mfpu=fpv4-sp-d16 \

-o MyBlink.ino.elf \

MyBlink.ino.cpp.o common_data.c.o main.c.o pin_data.c.o variant.cpp.o \

libfsp.a core.a \

-lstdc++ -lsupc++ -lm -lc -lgcc -lnosysAfter this step, the final binary will be MyBlink.ino.elf.

Take a look at libraries that are linked into the build:

libfsp.a→ the Renesas Flexible Software Package, providing hardware drivers and low-level functions for peripherals.core.a→ the Arduino core for this board. Libraries above are board support libraries. These are part of the Arduino board package (for the Uno R4 in this case). They are not optional user libraries, so they don’t appear in the detection phase.

Toolchain standard libraries:

-lstdc++→ the C++ standard library,-lsupc++→ low-level C++ runtime support,-lm→ the math library,-lc→ the standard C library,-lgcc→ helper routines from GCC itself,-lnosys→ stubs for system calls.

Finalizing build

Build is ready! Arduino will perform two more steps before finishing the process.

Creating binary and hex files

After the ELF file (MyBlink.ino.elf) is created, the build system uses objcopy to generate hex and bin formats:

arm-none-eabi-objcopy -O binary -j .text -j .data MyBlink.ino.elf MyBlink.ino.bin

arm-none-eabi-objcopy -O ihex -j .text -j .data MyBlink.ino.elf MyBlink.ino.hexBoth formats contain the same program, just encoded differently for different flashing tools.

Measuring the program size

Finally, the build system reports memory usage with arm-none-eabi-size:

arm-none-eabi-size -A MyBlink.ino.elfCleaning the build

Unfortunately, Arduino IDE does not offer the Clean build or Force rebuild option ([1],

[2],

[3]). The workaround for it is to manually delete the cached build directories we mentioned earlier.

Summary

- While it’s often called the Arduino language,

.inofiles are actually written in C++. They simply receive some automatic handling from the Arduino build system, and themain()function is predefined and hidden within a library. - Arduino build process follows standard C/C++ build steps, but adds some additions: automatically detects libraries that need to be linked, includes main header, generates function prototypes if they are not included.

- Arduino doesn’t use

Makeor any other common build system. Instead, it usesarduino-cliwhich constructs build commands based on recipies fromplatform.txtandboards.txt.